On a Tree

“We’ll make an army in the trees and bring the earth and the people on it to their senses.”

― Italo Calvino, The Baron in the Trees

On a day in June 1767, according to the story, Cosimo Piovasco di Rondò, twelve years old and future Baron di Rondò, rebelled against his illustrious father and ran from the lunch table.

In his most formal clothes and headdress—three-cornered hat, lace stockings, ruffles, green tunic with pointed tails, purple breeches—the boy climbed up the old holm oak and declared,

that he renounced his fortune; denounced his father’s injustice; denounced, in fact, all injustice. He would not eat that soup; he would live on the trees and be free and be able to “piss farther.”

On that tree, he looked around, saw the world; wider, better, truer than his father ever could. He saw land, vast and ripe with harvest and infinitely coloured. Orchards; plum and pear and cherry, strawberry, apricot. He saw the sky and sea in variegated shades of cyan, azure, cerulean, lapis, indigo, cornflower.

Then, he saw his father; small. People; warped and rooted, like trees, by their ideas. Wars, theft, and age and illness, hatred, sorrow,

and passing kings, armies, laws,

while life, also, passed them,

“and there, with naive youthful fervour, […] the ideas of the philosophers and the wrongs of sovereigns and how states could be governed according to reason and justice.”

The boy never came down from the tree. He spent his life up there, “for my ideals,” and at the end, hitched a ride on a passing hot air balloon, and flew away.

There are other ways, on the ground, to do good, denounce injustice, piss far, and live well and free. I know a man, for instance, who was a boy once, who climbed trees, still does whenever he can,

and when he can’t—or when war, theft, age, illness, hatred, or sorrow—

he goes on walks and gathers pine seeds,

plants them in orange pots he lines along a windowsill,

rises early on Saturday morning,

waters saplings,

prunes the larger apple, olive, pear, plum trees,

coaxes vines of syrupy golden grapes up trellises,

picks figs, deep purple and pastel white, bursting at their seams,

for his ideals, and with his naïve youthful fervour.

I know of knights errant, rebels, generals, and barons in trees. But also a man who, on a day in June, 1993, let a four-year-old climb up a pine tree. All the way to the top. His knees must have shook, but he just said:

Be careful. Don’t fall.

I knew I wouldn’t. He wouldn’t let me.

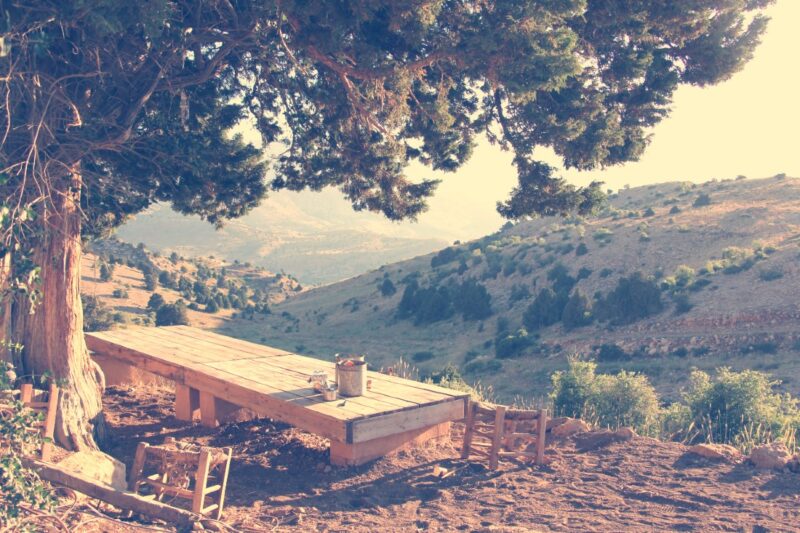

I know a man who never had the luxury to live on trees, but whose world is a garden, vast and ripe with harvest. In it, he plants plum, pear trees. Apples, figs, cherries, apricots, strawberries. Trees that will remain, or not, bloom, or not, next year.

A man with roots, who is not rooted; whose blues of sky and sea are shoreless and infinitely varied; whose freedom is to dig, and plant, and water, and reach,

and yes, “piss farther,” in spite of everything.