“My barn having burned down, I can now see the moon.”

— Mizuta Masahide (17th century Japanese poet and samurai)

Across the continents and seas, seven hours ahead of me, a voice on the phone says it must hang up; it is ten to nine p.m. Like a dark fairy tale, at nine on the hour, the power will be cut. No lights, phones, TVs, computers, internet connection.

When the power goes, for a moment, the circulation of a city’s blood stops.

Instantly, muted TVs, old fishbowl screens wiped out. Interrupted washing machines; clothes soaked, sudsy in barrels. No lights; neon signs, saffrony lampposts, honey and lemon and LED-lit kitchen and living room windows.

Pitch black. Ink black. No, ink is glossy; power cuts are thick and viscous. Tar black, in which the soul sinks. On the roads: shipwrecked cars, headlights flashing SOS—no traffic lights—desperate and quiet, even their radios silent; the local soft jazz station, 90.5, also interrupted.

I know that black. I know that place where people’s lives are run by power cuts,

and news bulletins and flashes—of speeches, demonstrations, strikes, and sometimes burning tires, Molotov cocktails, gunshots—puncturing time, segmenting it into hours, days whose rhythms they dictate, like the price of gasoline.

That of bread, subsidized, is fixed. So the people don’t starve. But they must shower in quick succession whenever there is hot water;

and vacuum and do laundry whenever they can, sometimes at four in the morning when the power is back;

and hoard staple foods on pay day, having queued at ATMs,

and reassure family abroad, on the phone, that all is well.

“Call us tomorrow?” says the voice, at five to nine.

“I’m sorry,” I say.

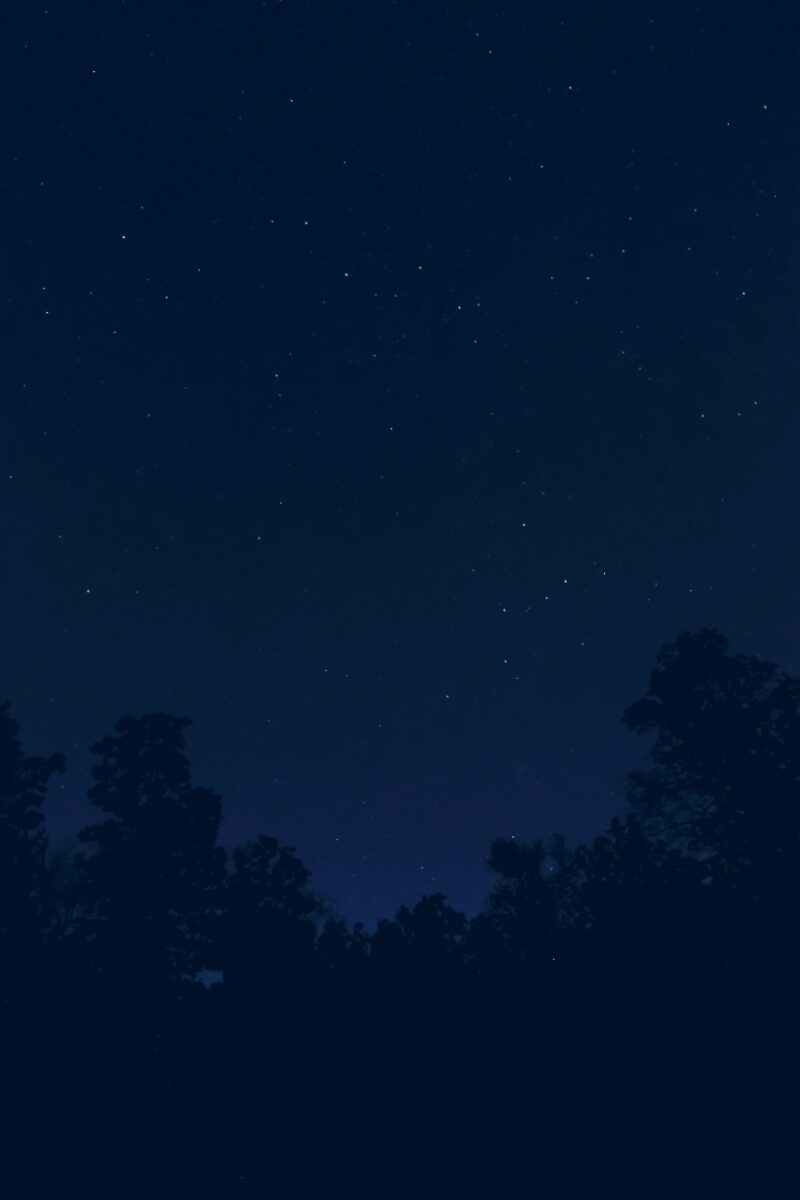

“Don’t be. I’ll go for a walk; when the power goes out, you can see the stars.”

I know a place where some men pour themselves whiskeys at nine, drowning the hour and the tally of the day’s disappointments. In the darkness, in a glass—tall, no ice, with just a thumb of water. I know women who stifle the pain with shortbread Scottish biscuits. Overly sweet and buttery, to mask the bitterness. In the silence, on the hour.

Stores are out of shortbread biscuits. And other imports: coffee creamer, milk, diabetes medication… frivolities in a spiraling, dissolving economy. Liquor never runs out, but the women now go through pack after pack of local, dry Ghandours; ten cookies per pack, ten packs per box, which costs… not much, but more than so many can afford in Lebanon.

I used to know how much Ghandour cookies cost. I knew the cost of living, of life in a country so small and battered. I knew the girl whose father put a bullet through his head. I knew words children should not; corruption, devaluation, RPGs, Katyushas,

But I was raised by people who would not let power cuts rule them.

I know we lived with abundance and always had plenty,

of friends over for meals, of which we had seconds and thirds while talk and laughter ricocheted over the kitchen table; of fruits and books and plans for trips we drew on yellowed maps and across the pages of thick, green, leatherbound atlases.

They were heavy. Everything was. I did not know that then; my parents carried them for me. They carried us to bed, tucked us in and read aloud; stories and fairy tales. Sometimes, on really dark nights, they invented them.

They gave us views of sky that stretched across continents and seas, horizons sparkling with light. They made sure we were safe, and asleep by eight-thirty.

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

Now I know all they did for us. All they do. Now I know, at nine on the hour, somewhere across seven time zones, the sound of that silence.

The occasional bark. Crickets. One’s own heartbeats, breath, its taste. I know the shades of black, until you look up, and see…

constellations.