“Life is short. From here to that old car you know so well there is a stretch of twenty, twenty-five paces. It is a very short walk.“

– Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita

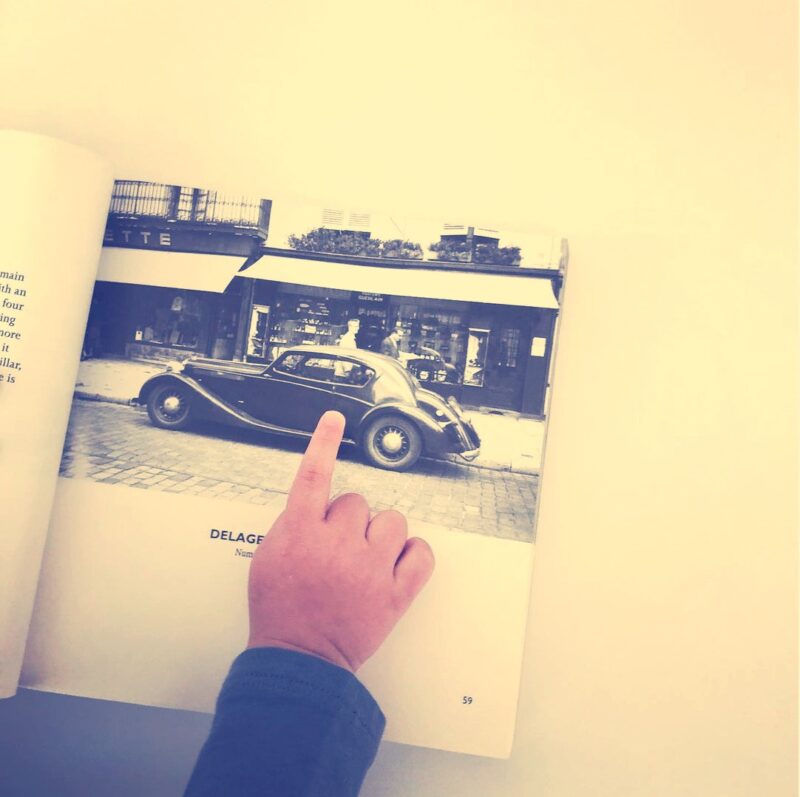

Among the many books populating a small Boston apartment, is one in Burgundy red entitled Classics on the Street: An Automotive Odyssey, France 1953. The book is moderately sized and medium heavy—a child could carry it with both hands—its cover worn but glossy, showing an equally shiny, black-and-white car parked on a Paris street.

Inside the book, there are a hundred such pictures, of cars and Paris—cars in Paris, entering, leaving it; cars and Parisians, in them, by them, walking past them—each on a separate page, waxen, creamy and luxurious under the fingertips. Beneath every photograph is the car’s make and model, and the month, year, and location the picture was taken.

Smudges and light tears on a page indicate a favourite:

A car in a field, at the outskirts of the city, by a river; a picnic spread, one bather, one dog, one napper. A car and a parc bench. A car and a parc bench on which a couple hold hands. Cars double-parked in front of a café. More cafés, brasseries. Ice cream shops. A car with children. One with a driving dog. A car next to which a young woman in a bell-shaped white dress is smiling at the camera, holding a baguette.

The book is banal. Most of the snapshots are of residential life on residential streets. Most of the cars are Peugeots; most of the people, lugging groceries. The book cost a dollar. The book is the most precious artifact in the entire apartment. It has been studied, memorized, taken to bed, to breakfast.

Classics on the Street: An Automotive Odyssey belongs to a pair of two-year-olds. It is the source of endless dreaming, much debate and power struggles. The woman in the billowy white dress, however, by consensus, has been pronounced Maman and allowed to partake in this adventure. Her tasks: arbitrage, interpretation of the pictures and the world—how large, scary, wonderful, variegated—and development of a field guide for its navigation. The following are some preliminary principles gleaned from this experience:

Never rescind a promise. Never lie or forget or feign to. Children build castles on words. Tomorrow means tomorrow. One more page means one more page. One more time, from the top: Page 1,

“Once upon a time… yes, those are strawberries. Tomorrow, we’ll buy a box.”

(Author’s recommendation: Tomorrow, buy two boxes.)

Always hold a book with both hands, never by one page. Always hold a child by the hand, never by the wrist. Pages rip, and little wrists can hurt and break. So can spirits. Never snap or snatch. Ask first, always. Wait for the answer. Listen. It can take anyone a moment. Some thoughts are big. Some words have a lot of syllables.

Look! Maman! Drop to the floor; some shelves are too high from there, some truths too daunting, some corridors too dark. Some legs are still short and some hearts are so fragile.

“Make those twenty-five steps. Now. Right now. Come just as you are. And we shall live happily ever after.”

And that book of vintage cars is an odyssey and treasure.