“He gave me what he could. Within his limits. He gave me books … and music…and drawing… and dancing … and French … and riding … and …”

– Mavis Gallant, What is to be Done?

There was once a shop, in Brussels, in a fountained, cobblestone square, called Princesse, which sold outrageously expensive, gorgeous dresses for little girls. Velvets, laces, silk, impractical whites, petticoats;

dresses that yellow in naphthalene boxes, waiting for the right occasion.

Next to the once-shop, there is, still today, an outrageously luxurious, gorgeous café, with a glass-covered terrace, pristinely white-gloved waiters, linened tables, floating in the glow of space heaters and faint, misting sound of a piano.

In the café, there are people, a certain kind of people, sitting, on a weekday, sipping foamy, pillowy, cacao-dusted cappuccinos,

reading, chatting, people-watching, some just listening to the piano and ambient sounds of morning. Buttering little breads with little knives, flirting with poached eggs, scooping yogurt, berries, picking up croissant flakes,

behind a barricade of lush, potted hydrangeas, on the other side of which,

the anxious, bedraggled, other kind of people commutes, rushes, each to some place,

chasing some time, place,

in which there would be the right occasion,

time,

place

for such an outrageously indulgent, gorgeous,

morning, existence.

The hydrangeas, still in bloom, in sky and royal blues, seem meant to match the perfectly tailored

navy suits; the peach lipsticks; cashmere coats; pearls and diamonds; silk, impractically fine, refined, thin for a day in December.

There is, at the third table from the door, a young woman looking at the menu, not in furs, alone. There was once, at that table, an older gentleman in an Ascot tie who had just bought a four-year-old a dress. A Princesse dress, deep blue velvet, red cherries, red bow, a starched collar and impractical, many-layered petticoat.

There was no reason, occasion for it, save the silver Brussels light that had caught the dress’s folds in the window, and his eye. In the shop, the little girl had spun in the dress. Her grandfather had applauded. She had kept wearing it.

They had walked out, he holding her hand, she in a dress too fine, refined for a four-year-old and day in December,

crossed the square, to the outrageously gorgeous café, and sat, she with two bolster pillows beneath her.

“What would you like?”

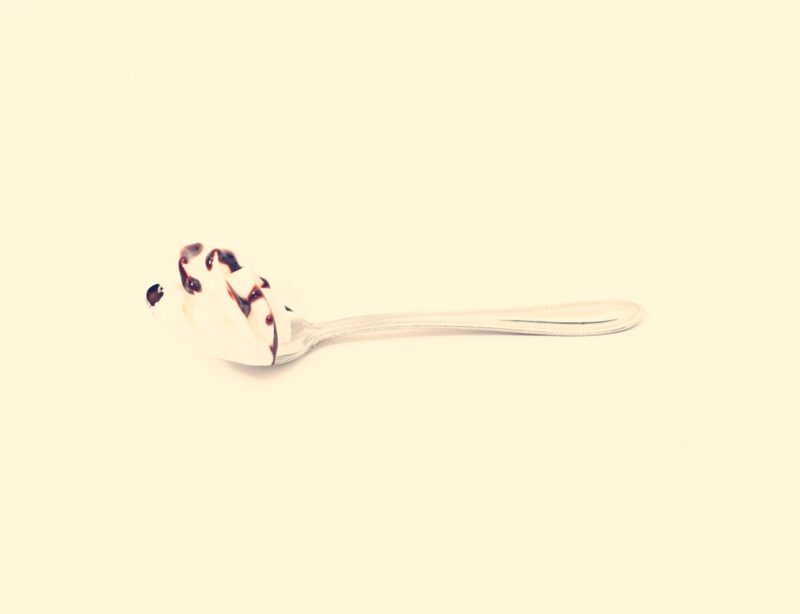

The white-gloved waiter had asked… her! That day, a princess had dessert for breakfast with her grandfather. He had a cappuccino, she, un banana-split, trois boules! Chocolate, fraise, vanille, topped with the puffiest, lightest, silkiest whipped cream; a cherry, Maraschino, red like those on her dress; and delicate chocolate drizzle,

that dripped onto the collar.

The shop and gentleman are gone. The stain is still there. The dress, in a box in a drawer. And, on the woman’s tongue, the taste of that dessert, morning, way of existence.

In the café, she sits now, in a cheap raincoat, blue, like the hydrangeas, looking out at the anxiously rushing, chasing people,

and orders an outrageously expensive banana split, and cappuccino.